Why I Don’t Use Those Valuation Multiples (and You Shouldn’t Either)

How those popular ratios could leave you astray

The basic idea of investing is very simple: buy low, sell high.

Easy to say, right? But putting it into practice? That’s where things get tricky.

A lot of investors use those common ratios and multiples – like EPS and P/E – to quickly decide if a stock is a bargain or not. But serious investors like you may want to think twice before relying too much on those popular numbers.

Let me explain in this article why.

Problem #1: Accounting Numbers Don’t Always Tell the Real Story

These days it is very easy to get those multiples, they are readily available everywhere. Many online sites are offering access to the company’s financial statements and those calculated ratios. But the thing is, those financial statements are based on accounting numbers, and those numbers don’t always tell the story what investors want to hear.

There are tons of reasons why companies might want to “optimize” their financial statements – things like saving on taxes or boosting management bonuses. I am not talking about fraudulant accounting. Even GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) allows certain flexibility on how certain costs are handled – whether they’re capitalized or expensed.

Let me give you a couple of examples:

Building a new factory: a company is building a new factory to scale up production. The associated cost is going to show up on the balance sheet first, and then it will go into the income statement as depreciation over a bunch of years. That way, the impact on earnings is spread out over time.

R&D spending: if a company invests heavily into developing a new product that will bring extra sales in the future, that’s rather treated as an expense. It hits the income statement right away in the year the investment was made. So, earnings take a hit that year.

Now, both of those investments are meant to do the same thing – boost the company’s future. But because they’re accounted for differently, they can give you a totally different impression of how the company is doing.

The financial statements you can readily access should only be the starting point of your business analysis. Thoughtful investors have a lot of work to remedy these serious accounting distortions. - Warren Buffett

Problem #2: Relying Only on Those Multiples Can Be Misleading

Let’s break it down with some examples.

Price-to-Book (P/B)

A lot of investors use the price-to-book ratio (P/B) to compare a company’s market value to its book value and try to find undervalued gems. You just divide the stock price by the book value per share.

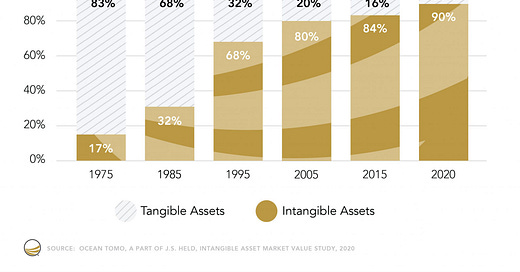

That made sense 30-40 years ago when a company’s value was mostly in its tangible assets. But things have changed over time. Today, like 90% of a company’s market value comes from intangible assets like goodwill and patents – and a lot of that isn’t even on the balance sheet, or it’s valued all wrong.

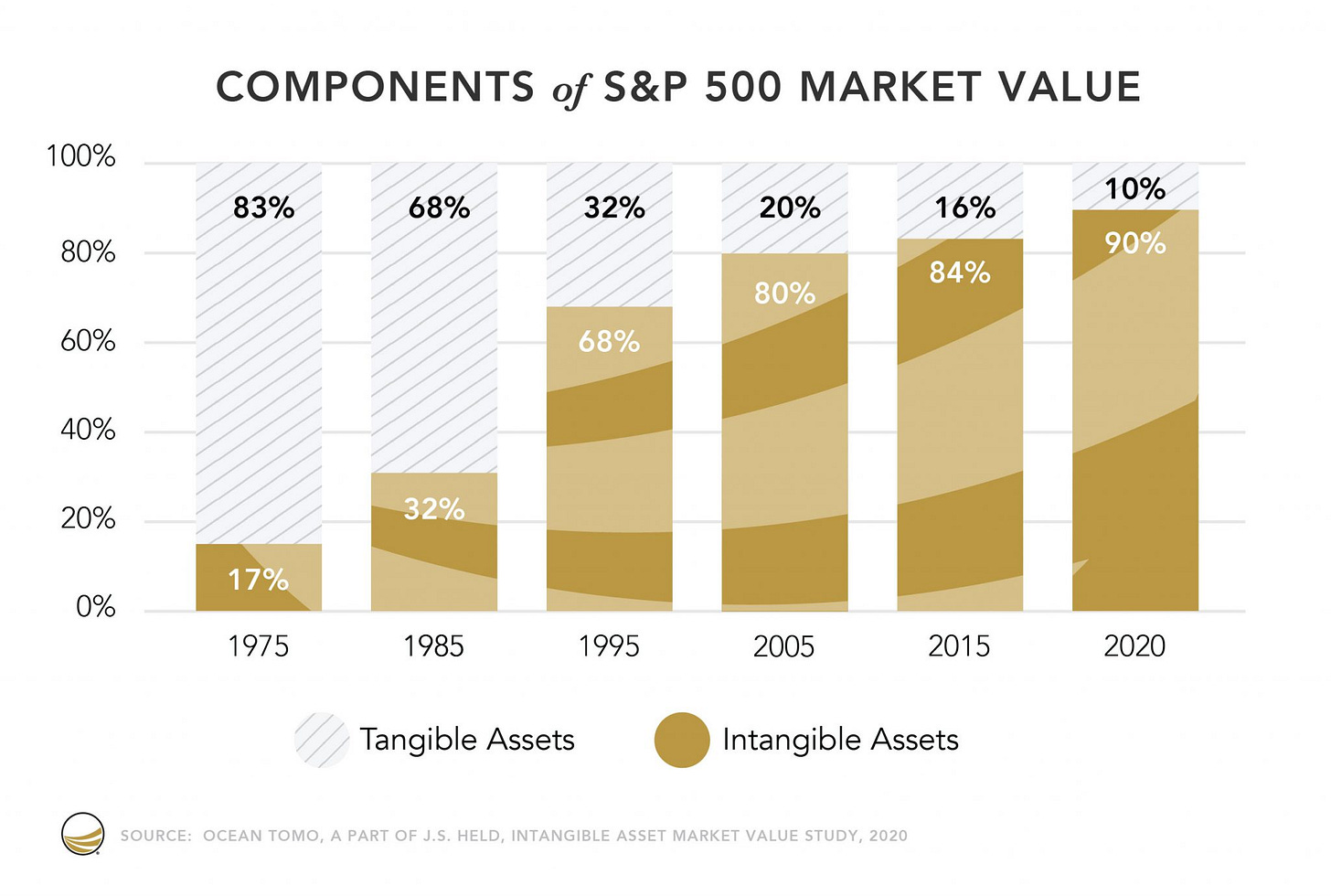

So, is this ratio still a good way to tell if a stock is cheap? Would you have bought Netflix back in early 2018 when its P/B was almost 38?

Price-to-Sales (P/S)

The problem with this one is that it doesn’t tell you anything about profitability. And profitability is what really matters.

Think about it: which one would you rather own, Company A or Company B?

Without knowing how profitable they are, the P/S ratio alone isn’t going to help you much.

Price-to-Earnings (P/E)

This one’s super popular, but it’s got its flaws too.

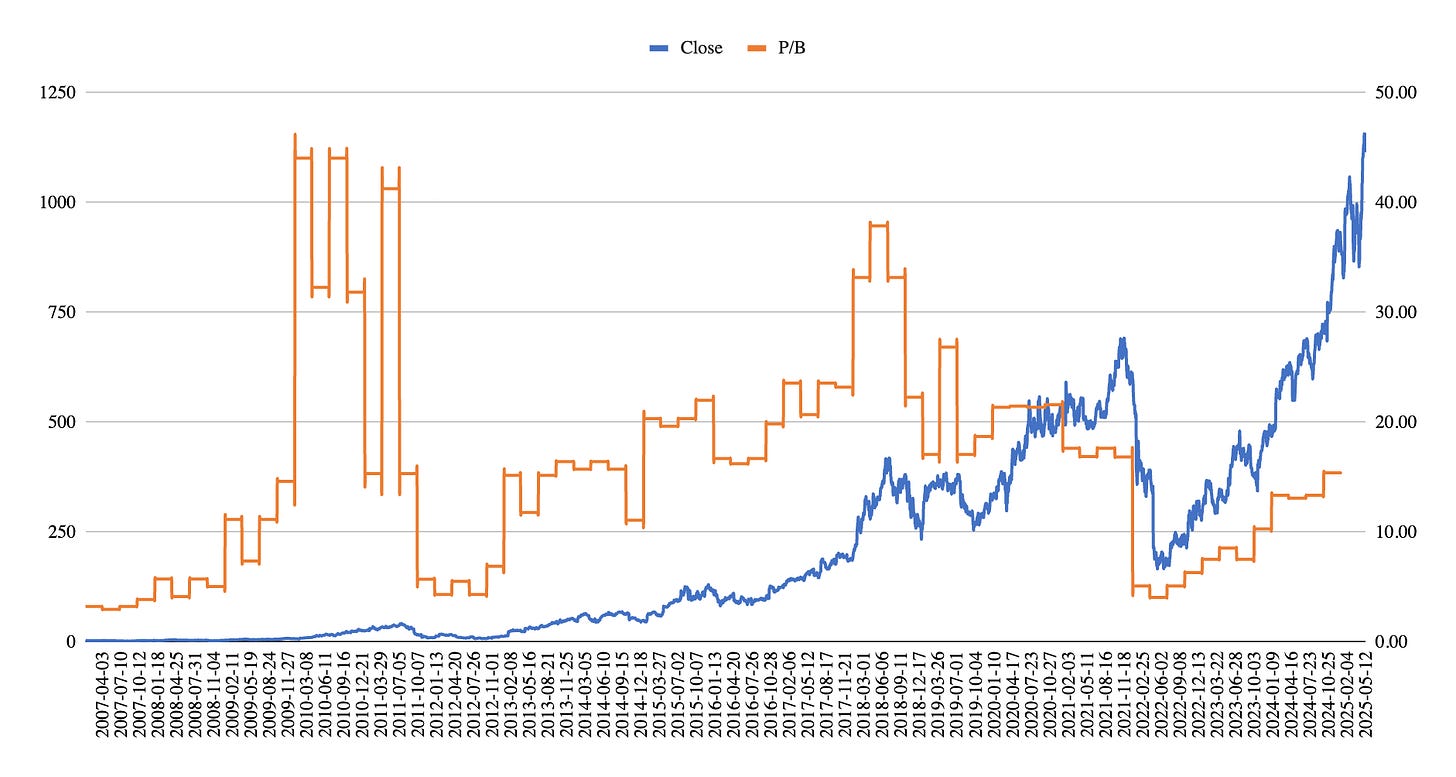

Let’s say a company makes $100 in net income in year one. The management decides to keep all of it and buy bonds that pay 4%, and they don’t do anything else. Over time, the earnings and the P/E ratio look better and better, and maybe by year five, it looks like a great time to buy the stock.

But would you be happy with that company’s performance? I’m guessing not. EPS is growing, but the company isn’t really creating any value.

Price-to-Free Cash Flow (P/FCF)

The more free cash flow a company generates, the lower the ratio, and the more attractive the stock seems. But that’s not always the case. A company could be sitting on in piles of cash and if the management can’t find good ways to invest it, the company isn’t creating value. On the flip side, there might be times when a company has tons of great investment opportunities, which makes the cash flow look lower or even negative for a while.

The Bottom Line

Most of those widely used valuation ratios can be misleading and don’t really show how well a company is creating value. So, you’ve got to forget about them or use them very carefully.

The best thing to do is skip the guessing game based on those multiples. Instead, dig deep into the company’s operations and make smart investment decisions based on that.

“There is no one easy method that could be simply mechanically applied by, say, a computer and make anybody who could punch the buttons rich. By definition, investing is going to be a game which you play with multiple techniques and multiple models, and a lot of experience is very helpful.” - Charlie Munger